The Soil Biology Primer

Chapter 7: ARTHROPODS

By Andrew R. Moldenke, Oregon State University

THE LIVING SOIL: ARTHROPODS

Many bugs, known as arthropods, make their home in the soil. They get

their name from their jointed (arthros) legs (podos). Arthropods are

invertebrates, that is, they have no backbone, and rely instead on an

external covering called an exoskeleton.

|

|

Figure 1: The 200 species of mites in this

microscope view were extracted from one square foot of the top two

inches of forest litter and soil. Mites are poorly studied,

but enormously significant for nutrient release in the

soil.

Credit: Val Behan-Pelletier,

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada |

Arthropods range in size from microscopic to several inches in length.

They include insects, such as springtails, beetles, and ants; crustaceans

such as sowbugs; arachnids such as spiders and mites; myriapods, such as

centipedes and millipedes; and scorpions.

Nearly every soil is home to many different arthropod species. Certain

row-crop soils contain several dozen species of arthropods in a square

mile. Several thousand different species may live in a square mile of

forest soil.

Arthropods can be grouped as shredders, predators, herbivores, and

fungal-feeders, based on their functions in soil. Most soil-dwelling

arthropods eat fungi, worms, or other arthropods. Root-feeders and

dead-plant shredders are less abundant. As they feed, arthropods aerate

and mix the soil, regulate the population size of other soil organisms,

and shred organic material.

SHREDDERS

Many large arthropods frequently seen on the soil surface are

shredders. Shredders chew up dead plant matter as they eat bacteria and

fungi on the surface of the plant matter. The most abundant shredders are

millipedes and sowbugs, as well as termites, certain mites, and roaches.

In agricultural soils, shredders can become pests by feeding on live roots

if sufficient dead plant material is not present.

|

|

|

Figure 3: Millipedes are also called

Diplopods because they possess two pairs of legs on each body

segment. They are generally harmless to people, but most millipedes

protect themselves from predators by spraying an offensive odor from

their skunk glands. This desert-dwelling giant millipede is about 8

inches long.

Orthoporus

ornatus.

Credit: David B.

Richman, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces. |

Figure 4: Sowbugs are relatives of crabs

and lobsters. Their powerful mouth-parts are used to fragment plant

residue and leaf litter.

Credit: Gerhard

Eisenbeis and Wilfried Wichard. 1987. Atlas on the Biology of

Soil Arthropods. Springer-Verlag, New York. P.

111. |

PREDATORS

Predators and micropredators can be either generalists, feeding on many

different prey types, or specialists, hunting only a single prey type.

Predators include centipedes, spiders, ground-beetles, scorpions,

skunk-spiders, pseudoscorpions, ants, and some mites. Many predators eat

crop pests, and some, such as beetles and parasitic wasps, have been

developed for use as commercial biocontrols.

|

|

|

|

Figure 7: This 1/8 of an inch long spider

lives near the soil surface where it attacks other soil arthropods.

The spider's eyes are on the tip of the projection above its

head.

Walckenaera acuminata.

Credit:

Gerhard Eisenbeis and Wilfried Wichard. 1987. Atlas on

the Biology of Soil Arthropods. Springer-Verlag, New York. P.

23. |

Figure 8: The wolf-spider wanders around

as a solitary hunter. The mother wolf-spider carries her young to

water and feeds them by regurgitation until they are ready to hunt

on their own.

Credit: Trygve Steen,

Portland State University, Portland, Oregon. |

Figure 9: The pseudoscorpion looks like a

baby scorpion, except it has no tail. It produces venom from

glandsin its claws and silk from its mouth parts. It lives in the

soil and leaf litter of grasslands, forests, deserts and croplands.

Some hitchhike under the wings of beetles.

Credit:

David B. Richman, New Mexico State University, Las

Cruces |

|

|

|

|

Figure 10: Long, slim centipedes crawl

through spaces in the soil preying on earthworms and other

soft-skinned animals. Centipede species with longer legs are

familiar around homes and in leaf

litter.

Credit: No. 40 from

Soil Microbiology and Biochemistry Slide Set. 1976. J.P.

Martin, et al., eds. SSSA, Madison, WI |

Figure 11: Predatory mites prey on

nematodes, springtails, other mites, and the larvae of insects. This

mite is 1/25 of an inch (1mm) long.

Pergamasus

sp.

Credit: Gerhard Eisenbeis and

Wilfried Wichard. 1987. Atlas on the Biology of Soil

Arthropods. Springer-Verlag, New York. P. 83. |

Figure 12: The powerful mouthparts on the

tiger beetle (a carabid beetle) make it a swift and deadly

ground-surface predator. Many species of carabid beetles are common

in cropland.

Credit: Cicindlla

campestris. D.I. McEwan/Aguila Wildlife Images |

|

|

|

|

Figure 13: Rugose harvester ants are

scavengers rather than predators. They eat dead insects and gather

seeds in grasslands and deserts where they burrow 10 feet into the

ground. Their sting is 100 times more powerful than a fire ant

sting.

Pogonomyrmex rugosus

Credit: David

B. Richman, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces. |

|

|

HERBIVORES

Numerous root-feeding insects, such as cicadas, mole-crickets, and

anthomyiid flies (root-maggots), live part of all of their life in the

soil. Some herbivores, including rootworms and symphylans, can be crop

pests where they occur in large numbers, feeding on roots or other plant

parts.

|

Figure 14: The symphylan, a relative of

the centipede, feeds on plant roots and can become a major crop pest

if its population is not controlled by other

organisms.

Credit: Ken Gray Collection,

Department of Entomology, Oregon State University,

Corvallis. |

FUNGAL FEEDERS

Arthropods that graze on fungi (and to some extent bacteria) include

most springtails, some mites, and silverfish. They scrape and consume

bacteria and fungi off root surfaces. A large fraction of the nutrients

available to plants is a result of microbial-grazing and nutrient release

by fauna.

|

|

|

Figure 17: This pale-colored and blind

springtail is typical of fungal-feeding springtails that live deep

in the surface layer of natural and agricultural soils throughout

the world.

Credit: Andrew R. Moldenke,

Oregon State University, Corvallis |

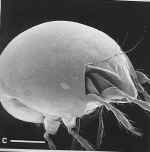

Figure 18: Oribatid turtle-mites are

among the most numerous of the micro-arthropods. This

millimeter-long species feeds on fungi.

Euzetes

globulus

Credit: Gerhard Eisenbeis and

Wilfried Wichard. 1987. Atlas on the Biology of Soil

Arthropods. Springer-Verlag, New York. P.

103 |

WHAT IS IN YOUR SOIL?

If you would like to see what kind of organisms are in your soil, you

can easily make a pitfall trap to catch large arthropods, and a Burlese

funnel to catch small arthropods.

Make a pitfall trap by sinking a pint- or quart-sized container (such

as a yogurt cup) into the ground so the rim is level with the soil

surface. If desired, fashion a roof over the cup to keep the rain out, and

add 1/2 of an inch of non-hazardous antifreeze to the cup to preserve the

creatures and prevent them from eating one another. Leave in place for a

week and wait for soil organisms to fall into the trap.

To make a Burlese funnel, set a piece of 1/4 inch rigid wire screen in

the bottom of a funnel to support the soil. (A funnel can be made by

cutting the bottom off a plastic soda bottle.) Half fill the funnel with

soil, and suspend it over a cup with a bit of anti-freeze or ethyl alcohol

in the bottom as a preservative.

Suspend a light bulb about 4 inches over the soil to drive the

organisms out of the soil and into the cup. Leave the light bulb on for

about 3 days to dry out the soil. Then pour the alcohol into a shallow

dish and use a magnifying glass to examine the organisms.

WHAT DO ARTHROPODS DO?

Although the plant feeders can become pests, most arthropods perform

beneficial functions in the soil-plant system.

Shred organic material. Arthropods increase the

surface area accessible to microbial attack by shredding dead plant

residue and burrowing into coarse woody debris. Without shredders, a

bacterium in leaf litter would be like a person in a pantry without a

can-opener – eating would be a very slow process. The shredders act like

can-openers and greatly increase the rate of decomposition. Arthropods

ingest decaying plant material to eat the bacteria and fungi on the

surface of the organic material.

Stimulate microbial activity. As arthropods graze on

bacteria and fungi, they stimulate the growth of mycorrhizae and other

fungi, and the decomposition of organic matter. If grazer populations get

too dense the opposite effect can occur – populations of bacteria and

fungi will decline. Predatory arthropods are important to keep grazer

populations under control and to prevent them from over-grazing

microbes.

Mix microbes with their food. From a bacterium’s

point-of-view, just a fraction of a millimeter is infinitely far away.

Bacteria have limited mobility in soil and a competitor is likely to be

closer to a nutrient treasure. Arthropods help out by distributing

nutrients through the soil, and by carrying bacteria on their exoskeleton

and through their digestive system. By more thoroughly mixing microbes

with their food, arthropods enhance organic matter decomposition.

Mineralize plant nutrients. As they graze, arthropods

mineralize some of the nutrients in bacteria and fungi, and excrete

nutrients in plant-available forms.

Enhance soil aggregation. In most forested and

grassland soils, every particle in the upper several inches of soil has

been through the gut of numerous soil fauna. Each time soil passes through

another arthropod or earthworm, it is thoroughly mixed with organic matter

and mucus and deposited as fecal pellets. Fecal pellets are a highly

concentrated nutrient resource, and are a mixture of the organic and

inorganic substances required for growth of bacteria and fungi. In many

soils, aggregates between 1/10,000 and 1/10 of an inch (0.0025mm and

2.5mm) are actually fecal pellets.

Burrow. Relatively few arthropod species burrow

through the soil. Yet, within any soil community, burrowing arthropods and

earthworms exert an enormous influence on the composition of the total

fauna by shaping habitat. Burrowing changes the physical properties of

soil, including porosity, water-infiltration rate, and bulk density.

Stimulate the succession of species. A dizzying array

of natural bio-organic chemicals permeates the soil. Complete digestion of

these chemicals requires a series of many types of bacteria, fungi, and

other organisms with different enzymes. At any time, only a small subset

of species is metabolically active – only those capable of using the

resources currently available. Soil arthropods consume the dominant

organisms and permit other species to move in and take their place, thus

facilitating the progressive breakdown of soil organic matter.

Control pests. Some arthropods can be damaging to crop

yields, but many others that are present in all soils eat or compete with

various root- and foliage-feeders. Some (the specialists) feed on only a

single type of prey species. Other arthropods (the generalists), such as

many species of centipedes, spiders, ground-beetles, rove-beetles, and

gamasid mites, feed on a broad range of prey. Where a healthy population

of generalist predators is present, they will be available to deal with a

variety of pest outbreaks. A population of predators can only be

maintained between pest outbreaks if there is a constant source of

non-pest prey to eat. That is, there must be a healthy and diverse food

web.

A fundamental dilemma in pest control is that tillage and insecticide

application have enormous effects on non- target species in the food web.

Intense land use (especially monoculture, tillage, and pesticides)

depletes soil diversity. As total soil diversity declines, predator

populations drop sharply and the possibility for subsequent pest outbreaks

increases.

WHERE DO ARTHROPODS LIVE?

The abundance and diversity of soil fauna diminishes significantly with

soil depth. The great majority of all soil species are confined to the top

three inches. Most of these creatures have limited mobility, and are

probably capable of “cryptobiosis,” a state of “suspended animation” that

helps them survive extremes of temperature, wetness, or dryness that would

otherwise be lethal.

As a general rule, larger species are active on the soil surface,

seeking temporary refuge under vegetation, plant residue, wood, or rocks.

Many of these arthropods commute daily to forage within herbaceous

vegetation above, or even high in the canopy of trees. (For instance, one

of these tree-climbers is the caterpillar-searcher used by foresters to

control gypsy moth). Some large species capable of true burrowing live

within the deeper layers of the soil.

Below about two inches in the soil, fauna are generally small – 1/250

to 1/10 of an inch. (Twenty-five of the smallest of these would fit in a

period on this page.) These species are usually blind and lack prominent

coloration. They are capable of squeezing through minute pore spaces and

along root channels. Sub-surface soil dwellers are associated primarily

with the rhizosphere (the soil volume immediately adjacent to roots).

ABUNDANCE OF ARTHROPODS

A single square yard of soil will contain 500 to 200,000 individual

arthropods, depending upon the soil type, plant community, and management

system. Despite these large numbers, the biomass of arthropods in soil is

far less than that of protozoa and nematodes.

In most environments, the most abundant soil dwellers are springtails

and mites, though ants and termites predominate in certain situations,

especially in desert and tropical soils. The largest number of arthropods

are in natural plant communities with few earthworms (such as conifer

forests). Natural communities with numerous earthworms (such as grassland

soils) have the fewest arthropods. Apparently, earthworms out-compete

arthropods, perhaps by excessively reworking their habitat or eating them

incidentally. However, within pastures and farm lands arthropod numbers

and diversity are generally thought to increase as earthworm populations

rise. Burrowing earthworms probably create habitat space for arthropods in

agricultural soils.

BUG BIOGRAPHY: Springtails

Springtails are the most abundant arthropods in

many agricultural and rangeland soils. populations of tens of thousands

per square yard are frequent. When foraging, springtails walk with 3 pairs

of legs like most insects, and hold their tail tightly tucked under the

belly. If attacked by a predator, body fluid rushes into the tail base,

forcing the tail to slam down and catapult the springtail as much as a

yard away. Springtails have been shown to be beneficial to crop plants by

releasing nutrients and by feeding upon diseases caused by

fungi. Springtails are the most abundant arthropods in

many agricultural and rangeland soils. populations of tens of thousands

per square yard are frequent. When foraging, springtails walk with 3 pairs

of legs like most insects, and hold their tail tightly tucked under the

belly. If attacked by a predator, body fluid rushes into the tail base,

forcing the tail to slam down and catapult the springtail as much as a

yard away. Springtails have been shown to be beneficial to crop plants by

releasing nutrients and by feeding upon diseases caused by

fungi.

Next

chapter: Earthworms ->

<Return

to the Soil Biology Primer home page

Back To Lychee Info

|